2017, AS A YEAR OF TRUTH

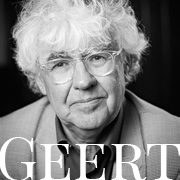

What went wrong with the European project, and when? Geert Mak looks, in the Geremek Lecture 2017, over the shoulder of the historian who will write about it, about half a century from now. 'Both historical projects, the United States and the European Union, are perhaps the most important legacy of the Enlightenment. It is a common heritage that we have to defend.'

In the summer of 2008 a car accident abruptly ended the life of a great man, a great European and also a prominent historian. Bronislaw Geremek embodied our European history like no other. He was the son of a Polish rabbi, has survived as a boy the Warsaw ghetto because he just could be smuggled out in time, was later professor of medieval history and gradually emerged as a leading figure in the Polish dissident movement. He was under Jaruzelski a year in prison, and after the Polish revolution he was Minister of Foreign Affairs and then, as a central figure in the European Parliament, a strong supporter of a united Europe.

I met him exactly ten years ago, during a series of Europe-lectures we organized in the Haque, at the Noordeinde Palace. Afterwards we mailed sometimes, we would meet again, there was too much to talk about, we knew for sure. And then he was dead. Yet Bronislaw lives often in my head, and certainly these weeks. He knew the things he was talking about, a Europe without law and justice, detached from any civil society, that childhood experience had shaped his life.

Like many others, Bronislaw Geremek converted these old fears into activity, in opposition activity and, later, diplomatic activity. He saw, even then, the 'no' in France and the Netherlands in 2005 as the tip of a much wider legitimation crisis that could have enormous consequences. "We can ask ourselves," he said, in his lecture in The Hague 'or not just a lack of mutual trust and sense of community lays at the root of the problems between the European Union and its citizens, and visa versa." And he warned us: it is not possible to have a democracy without a shared responsibility, without citizens who feel themselves members of a political community.

Geremek was very worried, allready in 2007. But I think that he, like the rest of us in 2007 in Palace Noordeinde, would be beaten with bewilderment if we could cast a glance at our Europe in 2017. Ten years later, and the euro is a financial and political nightmare, London prepares a Brexit, in Athens and Madrid almost half of the youth strolls unemployed around, heavily armed soldiers are patrolling in the streets of Paris and Brussels, around Sicily desperate economic and political refugees are drowning by the thousands in the Mediterranean, nationalist slogans set the tone, large-scale terrorist attacks boost fears, over and over again, twitter rages of hatred.

***

What went wrong, and when? I would love to look over the shoulder of the historian who will write about it, about half a century from now. He will, perhaps, begin with the democratic legitimation of the whole European project, an issue that was never addressed in a convincing way. The shaky political structure of the EU was the result, a system of treaties without, when necessary, the efficiency of a solid federative context. Within those limits the European politicians and diplomats proved, at the end, very good at setting rules, but the system was very weak – like Luuk van Middelaar explained very well - when it came to an effective response to events. It is very well possible that our future historian will give also a central role to the euro. This single currency without a common financial and economic policy put the eurozone under high-voltage, over and over again. Those crises were desastrous for the trust between north and south, and not only that. They took so much political energy, they were so long on the top of the European agenda that there was not enough attention anymore for all other sorts of, more positive, common issues.

The banking crisis of 2008 acted in this situation as a launch for three more fundamental crises: of the European project, of the democratic systems and of the globalization in general. With these three crises came also a massive psychological crisis, which no rescue plan could change. You could say that around 2008 both the Americans and the Europeans began to realize that they had moved from one society to another. From a society with a high degree of mutual trust to a society full of distrust, from a society of optimism to a society full of bad feelings, from a society in which certain truths and rules were allways in force to a society in which everything was uncertain. It was, in that respect, also an Atlantic crisis - perhaps the last.

Now, suddenly, America seems to retire from this part of the world. Like the new elected American president said in interviews before, in his own subtile way: ‘Our allies are making billions screwing us. Pulling back from Europe would save this country millions of dollars every year.’

This policy can become the end of the American empire, and it will be, for sure, a fundamental break with a political line of more than seventy years. That such a thing ever would happen was to be expected - even in this light participation in the JSF project was not so wise - but no one expected that it would be so fast and sudden. Europe had become lazy, relying on the eternal American umbrella. Border control and defense have been neglected for years. And now this protective umbrella collapses unexpectedly, we see how vulnerable we really are: on the southern flank a burning Arab world, on the eastern flank an aggressive and frustrated Russia which is very well capable to start, in the near future, a new armed conflict in Ukraine or, heaven forbid it, the Baltic States. These scenarios are, alas, not unrealistic.

Many European countries are, however, no longer accustomed to this kind of geopolitical problems - also by this endless American protection. We Dutch have, with that, a long history of looking away - we love to see ourselves as small and harmless. I get again and again the impression that many politicians, journalists and policy makers, bickering about lost receipts and electiontweets, still do not understand how dangerous the international situation is, for us all. There is a strong tendency to continue on as before, everywhere - yes, also in that respect, history repeats itself.

***

If you want to sit on top of the time, at the place where the history is forged, where you have to be at this very moment.? In the late eighties of the last century it was clear: Berlin, Brussels, Warsaw, Moscow. But now? Beijng? According to the columnist and writer David Brooks the most important spot on earth at the moment is, if you like it or not, again in the Oval Office in Washington DC. The crucial question will be settled there: can this new president be induced to govern in some rational manner, or he will blow up the world?

As I said, the crisis, the globalization, automation and the new technological wave, they created together another Europe and another America. On both continents started, in the same time, a growing discontent and even rage. For all differences - which are huge - there is one constant factor: British miners, French farmers, Dutch elderly or Polish villagers, they all feel abandoned and humiliated, forgotten by their leaders, left in the time.

The sociologist Karl Erikson described already in the seventies, the phenomenon of 'collective trauma', an event - the closure of a mine, a reorganization, the end of the classic village and farmerslife - which, apart from all economic and material consequences, meant a deep break with relationships and routines that had defined life there for generations. Without these social anchors people struggle to find again meaning and purpose in their lives, they feel often totally desoriënted and disconnected, and their deepest feelings can often be translated in four words: "Please, let's go home." "Let's go home, back to the good old days." And they follow every leader who promises to bring them home again. But there's no home anymore.

In America those feelings blossom especially in the so-called 'fly-over country, the unseen families in the poverty-stricken middle of America. When I, in 2010, crisscross traveled through the country for a travel story in the footsteps of John Steinbeck, men and women always told me again how they lived in Steinbeck’s days, in the sixties in a modest way, but they had jobs and security, and they were full of hope that life would become better for themselves, and especially for their children. Now that's changed completely. They are now full despair and bitterness, they lost forever the American dream that promised so much, and which, in their case, dilevered nothing.

The new American president is the product of that untamed fury. Some politicians and media treat Donald Trump still as a "normal" president with a few strange habits, comparable to Richard Nixon, George W. Bush or Ronald Reagan. However, such an approach is entirely misplaced. A presidency as his is, through all American history, unprecedented. Every politician must sooner or later face the transition from mobilization to power formation and to exercise of power. This is often difficult, every statesman has its own problems in the beginning. With Trump, however, this transfer is not happening at all. A president who doesn’t accept the basics of the constitution and the verdicts of independent judges, a president who gets, within 25 minutes, involved in a blazing row with the oldest and most loyal American ally, Australia, such a president is not a strategist, not a statesman, but only a big security risk.

However, this is more than a black comedy which became, suddenly, reality. When he took office, this new American president held a strikingly bitter inaugurationaddress. Every historian who know his literature sat up immediately when he heard it: here it happened again, here was again a leader who proclaimed a magical alliance between him and 'the people' to the exclusion of all other forces that make democracy a democracy: elected politicians, the judiciary, the press. It was a speech in which he laid the foundations for a totalitarian system. Not Republican, not conservative, but ethnic nationalistic, a polici based on the idea’s of the alt-right supporter Steve Bannon, Trump's closest advisor. 'We are at war,’ noted Bannon, time after time in his radio show, and he talked about a global, existential war – in line, also with the apocalyptic visions of the fundamentalistic christians in the American heartland. A war with the radical jihadis and with China, Bannon said. But, above all, without saying that, with the principles of the Enlightment. Now we can wait for the so-called Reichstag moment, a terrorist attack, an exchange of fire with the Chinese or other serious incident. Then the brake’s are off. And in Europe the echo becomes stronger too, every week.

***

2017 can so become a year of truth.

Both the United States and, later, the European Union can be considered as major historical projects. Projects of free citizens, who try to take the course of history in their own hands. Both are projects, rooted in the ideals of the Enlightenment, the ideals of human rights, the ideals of freedom, equality and brotherhood - and international brotherhood. These were, besides patriotism, the general European values which inspired the Dutch resistance against the totalitarian enemy during the occupation, values that inspired in the same way the heroïc Polish resistance the brave Polish soldiers and officers who fought and fell for our liberation. We must never forget that. But now both historical projects, perhaps the most important legacy of the Enlightenment, are severely threatened. It is a common heritage that we have to defend.

For decades, many of us lived in the illusion that progress, democracy and spiritual freedom went hand in hand. That appears no longer to be the case. It is possible that a gouvernment that emerges from a free and fair election demolishes the foundations of that same fair democracy. We, Europeans, have a shared history, more then we realize. Part of this history are not only the First and the Second World war, but also the turbulent years in between, the twenties and the thirties of the last century.

Can we compare, from a historical viewpoint, those years with what happening now? In a lot of aspects, the differences are huge. We are, to begin with, living in a totally different time. The National Socialism was despite all its atrocities, a modern movement which embraced modern life, it tried to bring its own kind of order in a complicated new world. Trump lives on chaos. He and his European followers actually lead nostalgic movements, movements that want to fly back in time.

But sometimes, when you compare both phases in history, the answer is clearly: yes. Steve Bannon, for instance, is strongly influenced by the theories of the Italian fascist Julius Evola. The American president himself uses the old "stab-in-the-back legend ' again with great skill, the alleged betrayal of the elites who are responsible for everything. His war rhetoric and ethnic nationalism fit seamlessly into the brown tradition – the American neo-Nazis love him, not without reason.

We should, so, not underestimate the self-destructive possibilities of the contemporary democracy,. A new term for this phenomenon is introduced: the "illiberal democracy", the stripped and unfree democracy that is not passed into a dictatorship - and perhaps never will do. For me this term is to kind. An 'illiberal democracy' is in my opinion a contradiction in terms. The miracle of democracy is the peaceful transfer of power, again and again, with every new election. The majority may have the power, the minorities can accept that because the majority continues to respect the rights and freedoms of the minorities. For the minorities remains also the perspective of change, of a new peaceful change of power. A democracy is, so, always in motion, there is always tension and debate – and that is why a free press is vital for any democracy. And, of course, a judiciary that protects those freedoms. A ‘illiberal democracy’, in other words, does not exist.

***

A man like Bronislaw Geremek, can we still look him in the eye? Or is it already too late with our populist ease, and with the growing carelessness about the fragile values of our perhaps most precious heritage, the immense European peace and modernization project of the last half century?

Farout the most Europeans are, thank God, still convinced democrats. And a man like Trump is not Putin or Erdogan, he does not act in a tradition of czars and sultans. On the contrary. He operates in the democratic context of the American Founding Fathers who designed nearly two and a half centuries ago a system that, through all kinds of ‘checks and balances,’ just was designed for this situation: to cut off this kind of totalitarian leaders. When someone enters a democratic public office, he does not swear to defend a person but a constitution, a set of principles. The Americans, like most of the Europeans, don’t swaer an oath to a person but to the Constitution, a set of democratic principles. Now our democratic systems, both in Europe and in the US, have to show that they still function, despite polarization and corruption. Like the historian Timothy Snyder is saying all the time: ‘Strong institutions are our only protection against barbarism.’

It is also our own personal struggle, and the urgency is great. It is, in this fight against the new totalitarianism, not any more about left or right, or north and south, or east and west. It is, frankly, about our fundamental values and freedoms. Every democrat, every free citizen, will now have to concentrate on that.

Again, many cultural fault lines within the European Union will become visible. In particular around the relationship between citizen and state - a relationship that has a different history in every European country. An Italian has a totally different attitude toward his government than a Briton or a Dutchman, a Western European has another kind of trust in the state than someone from Eastern Europe. The same applies to the concept of sovereignty: here it is old and established, in other parts of Europe it is the result of bloody fought bloody battles, even recently.

We, Europeans, can no longer escape these conversations and discussions. There is a cold wind blowing now, around all of us. It is like a marriage: at a certain point you have to watch each other really in the eye. From the very beginning the European project was built on the principles of the Enlightenment, on the rule of law, on democracy and freedom of expression. These were the values Bronislaw Geremek embraced, again and again, partly because all his childhood experiences. In these times the European Union cannot go on as before, designing common rules as allways. The Union must, increasingly, also respond to all kinds of unexpected events and developments. That means that, more than ever, we need to find a common political line. Yes, the Union has to develop a kind of common political community, the community Geremek talked allready about. And that community can only be based on a number of commonly shared basic values. We can no longer ignore it. Just like an ‘illiberal democracy’, an ‘illiberal European Union’ is impossible.

This year, 2017, is the litmus test. It will be very difficult. Does the Union, with its ups and downs, survives this storm, then there is hope for the future. But the old reflexes are strong, and if the member states, under influence of the nationalistic tide, embrace them more and more, then the great European experiment over. What will rest is, probably, a free trade zone with, for the happy few, the silver lining of a sort of euro or new D-mark.

There is, despite everything, still reason for optimism. Europe has still an enormous attraction, everbody want to belong, no one turns away from it. The joint responsibility which Bronislaw Geremek mentioned became a reality: in addition to all these European institutions we, European citizens, have created an European reality, a reality of countless networks of companies and people, an immense European fabric of contacts and exchanges. No crisis can take that away..

These months will ask again the extreme of the European leaders, particularly their ability to improvise and their flexibility, now that the European institutions are so poorly rigged for what is to come. The Union cannot longer effort cheap stunts and prestige conflicts. These months will also ask a new attitude from us, European citizens. The easy years are over. We must, as once Bronislaw Geremek, convert our fears into activity. We must be sharp, alert, we must vote. We must listen to our fellow citizens, react on their needs, win back their hearts and minds. We must, at this moment, especially defend our institutions. And above all: we must never let each other go.

GEREMEK-LECTURE 2017. GEERT MAK, FEBRUARI 14 2017