1914: Tears and a few afterthoughts

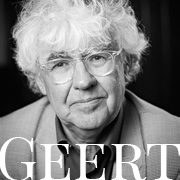

Was, what happened in the summer of 1914 a terrible coincidence. Or was it the result of more structural and human flaws, which can repeat themselves? Geert Mak’s keynote speech for the Europe 14/14, a project of the Berliner History Campus.

I stood looking at it for a very long time, years ago now: a small, mothy hole in the collar of a sky-blue uniform. It was on display in a glass case at the army museum in Vienna. The rest of the uniform was covered in bloodstains, the front and sleeves torn, each rent a silent witness to the panic of the doctors, their struggle to do everything they could to save him. The hole was right next to his general’s star. It was no more than a few millimetres across, yet it was that hole, that bullet, that plunged our continent into a hell of death and destruction that determined the life and fate of generations, the first shot fired in the Great European War that raged, with the intermezzo of a shaky peace, from 1914 to 1945.

We humans have an irrepressible tendency to equate, one way or another, the unknown with the impossible. We’ve never experienced it, never seen it, so it’s not there. And we aren’t at all happy if new ‘knowledge’ upsets our established order too much. That’s true now and it was true back then.

It was a golden age. Technology was capable of anything, everyone lived in a euphoria of novelty, year after year: the speed of trains and automobiles was breathtaking, the invention of the telephone a miracle, chemistry and physics pure magic. Electric light liberated everything in the house from gloom and menace. Cities like London, Berlin and Paris crackled with optimism and vitality. Wars between such blessed and civilized nations as ours were seen more and more as an impossibility.

I remember spending days on end during that same Vienna expedition working through the files of Die Neue Freie Presse in the National Library, purely to gain an impression of how the average European citizen experienced the mounting catastrophe in the summer months of 1914. It was an astonishing experience: even in summery Vienna, at the heart of the gathering storm, life continued on its normal course for weeks. Acute attention was paid to the pistol shot and the bullet hole, of course, to the murder of the crown prince and his wife in Sarajevo, but soon the front pages were dominated by the issue of whether protocol had been properly observed during the funeral ceremony. Then the Stock Exchange went on holiday, followed by the townspeople and their rulers, the sales started and through it all, day in and day out, sounded the iron rhythm of the classified ads: ‘Feschoform. Wirkt enorm. The true Viennese attributes her ample bust to Feschoform Bosom Balsem.’ Not until late July did disquiet emerge in the columns of the newspapers, and it wasn’t until the 26th that the word ‘war’ first surfaced. A week later the mobilizations were fully underway. Suddenly, within a few days, all the switches had been thrown on the machinery of war, which nothing and no one could stop.

My elderly Aunt Maart once told me how news of war wafted into my grandparents’ house in the little Dutch town of Schiedam. She remembered a hot summer’s day – she was a little girl of six – on which all the church bells suddenly started ringing. She walked home from school. In the working-class neighbourhoods people were standing outside their doors talking, a few of the women wiping their eyes on the corners of their aprons. A cheerful man called out excitedly to another: ‘It’s war, mate. England against Germany and mobilization for us.’ Everywhere the children were silent, none of them running or shouting, as if they knew intuitively that something was terribly wrong.

It must have been like that all over Europe: silent children, a few sniffling women, and in their midst all those cheerful men, filled with the optimism felt everywhere at the time, calling out to each other that they were off to get the job done, that they’d be home by Christmas and then Europe would steam on ahead into a golden age.

Almost all of us now have some idea of the causes, and in the run-up to this centenary commemoration they’ve been weighed up and pored over once again by historians: Russia, which was unable to control its difficult satellite state Serbia; Austria-Hungary, which responded to the murder by sending Serbia an ultimatum it couldn’t possibly accept; Germany, which then supported Austria to the hilt; France, which stood by its alliance with Russia; a procrastinating British government that took too long to clarify the British stance, both towards its allies and towards potential opponents; a weak Russian tsar who, under pressure from senior ranks in the army, was the first to set the machinery of mobilization in motion, after which other countries had no choice but to follow; and the fate that befell almost all Europeans after that.

So the most powerful heads of state and political leaders collectively blundered into the Great War, in many cases urged on by an enthusiastic public and an army leadership that was no less keen. As British historian Christopher Clark writes, they were ‘sleepwalkers, watchful but unseeing, haunted by dreams, yet blind to the reality of the horror they were about to bring into the world’.

There were exceptions. In Brussels the leaders of the socialist international made one final attempt to turn the nationalist tide. French socialist leader Jean Jaurès embraced German socialist Hugo Haase, both of them deeply moved. Here in Berlin the industrialist and politician Walther Rathenau sat in his chair silent and defeated, tears running down his cheeks. The British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Edward Grey muttered that same evening that the lamps were going out all over Europe. ‘And we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime.’

Could all this happen again? It’s a question often asked in these weeks, and with good reason. At first sight the answer is a clear ‘no’. The combination of circumstances that arose in July 1914 was so unique and complex that it’s unlikely to recur. On top of that, the countries of Europe are far more closely knit than they were a century ago. Wars between states, which broke out frequently in those years, have become rare.

But if you ask me whether it’s possible to recognize certain mechanisms today, and whether the spring of 1914 might resemble the spring of 2014 in some ways, then my denial is rather less categorical. I’m thinking of three phenomena in particular.

First there is the hijacking of politics. By that I mean an unexpected and abrupt takeover of the political decision-making process by a very different force field, by a system with totally different priorities, totally different values and totally different concerns. We saw something like it recently during the euro crisis: suddenly the laws and mechanisms of the financial markets took over European politics, and we’re still trying to get those particular genies back in the bottle.

In 1914 the genies were the war scenarios, vastly detailed war plans prepared by all the great powers over the preceding years, as meticulous and precise as railway timetables – and they were in fact closely bound up with the railways. If you wanted to move millions of men quickly to specific positions then you needed to work out the exact capacity of the relevant roads and railways, and decide how many days it would take to seize a given fort. Anyone arriving at the front a week late had already half lost the war.

This inflexible military planning had catastrophic consequences in the political sphere, since as soon as one power started to march, none of the others could afford to be left behind. The war scenarios therefore worked as hugely powerful engines, as predictions that turned themselves into reality. Only the strongest of politicians, true statesmen, can counteract a mechanism like that. And in 1914 few if any of those were around.

Are there other things we might recognize from 1914? Yes, certainly. I’m thinking in particular of our overestimation of the present day, of unending progress, of the permanence and eternal validity of contemporary values, combined with our underestimation of the power of the past. Russian dreams about a great and mystical nation, the brutal nationalism of the European populists – thoroughly nineteenth century, all of it, and at the same time these are very much signs of our times. The same phenomenon was part of the drama of 1914: the uniforms, language and dreams were still those of the eighteenth or nineteenth century whereas the technology – gas, tanks, aircraft, machine guns – belonged absolutely to the twentieth. And not only the technology; that blind optimism was thoroughly twentieth century too, including ‘home by Christmas’. Yet the eighteenth and nineteenth century were also part of it and that was no extravagance or mistake, it was an essential component of the thinking of the time, as it is now. Modernity is a thinner layer than we like to imagine.

Finally there’s the mystique we still wrap around disaster and war. It’s something we see in all countries and all eras: the irrational collective myths that all too often dominate public debate, the political leaders vilified as devils or venerated like mediaeval heroes. ‘There is a subterranean river of untapped, ferocious, lonely and romantic desires, that concentration of ecstasy and violence which is the dream of the nation.’ That was how Normal Mailer described the election campaign of John Kennedy, but you could write something similar about Russian, Ukrainian, Greek, French, Danish or Dutch nationalists, or about the cheers and flowers with which European citizens waved off their sons and loved ones in August 1914 as they left on the trains to hell. There seemed to be no rationality at all. To a sober observer it’s clear that none of the participants had anything to gain from war in 1914, except perhaps Russia, eager to annex Istanbul. Intoxication proved stronger. Christopher Clark makes an interesting point: not only were each and every one of the main players in this drama men, they were wedded to a culture of masculinity that was impossible to escape: ‘Uprightness’, ‘Backs very stiff’, ‘Firmness of will’, those were the key phrases.

Men were not alone in being enthralled by this kind of language and mystique; women were as well. Here in Berlin even the sensitive artist Käthe Kollwitz with her strong social conscience was carried away by it all. Her two sons reported for duty. She had her doubts, yet according to her diary, when her family gathered for a final evening together they sang ‘old landsknecht songs and war songs’. The next day the two boys left for the front accompanied by ‘enthusiastic singing’. ‘Glorious youngsters,’ she writes. Barely two months later her younger son was in his grave.

I’ll never forget the story an elderly lady here in Germany once told me when I was on a reading tour. Her grandfather had fought in that war, surviving Verdun and the trenches, but only just. At one point he found himself face to face with a Frenchman and managed to stab him first only because he was slightly quicker. The man squirmed briefly and then he was dead. His tunic fell open, revealing a wallet. Her grandfather picked it up and opened it to find several letters, a photograph of a girl and an identity document. The Frenchman was from Lille, I believe, and his name was Jean Claude. From that moment on, the old lady said during the reading, Jean Claude was a perpetual presence. ‘He stood next to my grandfather on his wedding day, when his first child was born, when he was appointed company director, when his grandchildren were christened: at all the important moments of his life this Frenchman was there beside him. And of course he came and stood in a corner of the room when my grandfather died.’

Whoever kills, kills part of himself. Whoever wounds, wounds himself too. The summer of 1914, that sunny, promising summer, turned out to be the edge of a deep fault line that runs across European history. The optimism of the first decade of the twentieth century, with its ideas about lasting international cooperation, about a shared European culture and economy – suddenly all of that seemed to be over. The great French champion of peace and international justice Jean Jaurès was assassinated in those weeks, and later Walther Rathenau met the same fate. Their voices were no longer heard, nationalism and the demand for revenge set the tone in European politics for decades.

Edward Grey’s prediction was right: not until 1945 did the lights go on again in Europe, and the continent was divided by an Iron Curtain for another forty years. Yet after 1945 something extraordinary happened. We often forget, but 1914 also meant the end of the established European order. The system of sovereign states that had more or less determined the structure and balance of power for centuries, since the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, failed catastrophically that summer.

It was a lesson the Europeans took to heart. In the 1950s Western Europe developed a completely new way of determining the relationships between states, a unique system that gradually expanded to cover most of the continent. It’s a system of supranational institutions, which doesn’t rely on troops and closed borders to create security but instead on openness, good relations, cooperation and the power of persuasion. Yes, that’s right: the famous soft power of the European Union. It was and remains a historical experiment of unprecedented magnitude, with all the errors and inadequacies that can become attached to it, but at the same time it’s a miracle, the great miracle of that war-ravaged Europe. And we must not allow it to be taken away from us by a new roll of drums.

Ladies and gentlemen,

Whoever kills, kills himself. Whoever wounds, wounds himself. That holds true for people and it holds true for nations as well. After 1945, after the Great European War, silence fell, a deep silence. A mist of shame moved in over great swathes of Europe. In the second half of the twentieth century extraordinary things happened, especially surrounding the European Union, but it seemed we could take no pride them.

It was a kind of paralysis, along with a speechlessness that lasted for years and was only slowly broken through. That phase is over now, which is one reason why initiatives such as this History Campus are so inspiring and important. Hardly anyone here in this room took a conscious part in the Great European War, but let’s face up to it: we are all the children, grandchildren and great grandchildren of two or three severely traumatized generations of Europeans. Sitting here now, all too many of us are children of survivors, of disabled grandfathers, gassed relatives, bombed-out aunts and uncles, of families torn apart or grandparents suffering endless nightmares, of parents with concentration camp syndrome, veterans of Normandy, Monte Cassino, the Ebro and Stalingrad, of the talkers and the silent, of mad fathers up in the attic. How much has that summer of 1914 ultimately shaped our own family histories, our own lives, our politics, even now, a century later?

Come tonight with stories told

About how war is long gone by

Repeat them all a hundredfold

Each and every time I’ll cry.

That’s a poem by a fellow Dutchman, Leo Vroman. Yes, we Europeans will have to keep telling each other all those stories, again and again. It’s the only way to understand one another, find one another again, comfort and embrace one another, the only way to forge that common past once and for all into a common future.

BERLIN, MAY 2014.