What about The Netherlands

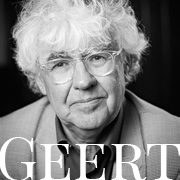

Geert Mak’s lecture in de USA about the Dutch: the moral panic after the murder of Theo van Gogh, Pim Fortuyn and the collapse of the pillar-system, the globalisation and the Dutch big-city problems.

Geert Mak’s lecture in de USA about the Dutch: the moral panic after the murder of Theo van Gogh, Pim Fortuyn and the collapse of the pillar-system, the globalisation and the Dutch big-city problems.

The lamentations of Coenraad van Beuningen

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I would like to take you to Amsterdam this evening, and to the broad, shimmering river Amstel which flows slowly into the city. It’s a wonderful place to go for a walk on sunny afternoons, especially on the left bank, between the arched bridges of the Herengracht and the Keizersgracht, past ships and the façades of bourgeois palaces built by rich seventeenth-century merchants. Take a good look at the sandstone wall of number 216, though. At first sight it appears to be covered in graffiti. It’s so difficult to get rid of that dreadful stuff. But look again, those thin red lines aren’t tags, they look like drawings of old ships with sails and flags. And look there: stars, Hebrew letters and Kabbalist symbols. And there, very faint, something that resembles a name: ‘Van Buenige’, and a few more letters that look like ‘Jacoba’…

I would like to take you to Amsterdam this evening, and to the broad, shimmering river Amstel which flows slowly into the city. It’s a wonderful place to go for a walk on sunny afternoons, especially on the left bank, between the arched bridges of the Herengracht and the Keizersgracht, past ships and the façades of bourgeois palaces built by rich seventeenth-century merchants. Take a good look at the sandstone wall of number 216, though. At first sight it appears to be covered in graffiti. It’s so difficult to get rid of that dreadful stuff. But look again, those thin red lines aren’t tags, they look like drawings of old ships with sails and flags. And look there: stars, Hebrew letters and Kabbalist symbols. And there, very faint, something that resembles a name: ‘Van Buenige’, and a few more letters that look like ‘Jacoba’…

We’re standing in front of the House with the Bloodstains. That’s what it’s been called since time immemorial. It used to be the residence of the rich merchant, mayor, and leading diplomat Coenraad van Beuningen. The inscriptions were almost certainly made by the owner himself, during the last years of his insanity. It’s three-hundred year old graffiti, the last desperate cries of a man seeing his world crumble around him.

In the second half of the seventeenth century Coenraad van Beuningen was one of the most important figures in Dutch politics. He was six times mayor of Amsterdam, director of the Dutch East India Company, envoy of the Republic in Stockholm and Paris, and William III’s crisis manager in the crisis year of 1672, when the country was attacked simultaneously by the French, the English and the Bishop of Münster. Partly due to Van Beuningen’s diplomatic skills, the Stadholder managed to save the country. Shortly afterwards, however, Van Beuningen and the Stadholder fell out and, embittered, Van Beuningen withdrew to his house on the river Amstel.

Was this rude treatment the beginning of the European diplomat’s downfall? We can only guess. Shortly after the affair, Van Beuningen fell under the spell of two sombre preachers and, to make matters worse, the old man wanted to marry. His chosen one was a posh Amsterdam lady of dubious reputation, Jacoba Bartolotti van den Heuvel, who lived round the corner. She turned out to be a serpent, and his marriage brought him nothing but misery. He began speculating on the stock market, lost his money, began seeing visions of fire and coffins in the night sky above the Butter Market, his wife left him, and he ended up wandering along the cold, quiet houses of the Amstel on winter nights, ranting and raving about the ‘unspeakable lethargy’ of the bourgeoisie. He wrote his messages on the façade of his house in his own blood. He died in poverty on 26 October 1693, leaving ‘a cape and two dressing gowns,’ a bed, some chairs, a desk, an oval shaped mirror, four old taborets and ‘a man’s portrait’ by Rembrandt valued at seven guilders (three dollars).

We’ll never know what demons drove Coenraad van Beuningen: depression, Jacoba, heaven, hell or other things. One thing is certain, however, one of them was politics. Or, to be precise, the spiritual and moral state of his city and the Republic at the end of the seventeenth century. For no matter how hysteric his delusions seemed, the concerns he shouted over the Amstel in the quiet hours of the night were, in essence, serious and real. His unique world had, indeed, gradually developed a deep identity crisis.

Part of this crisis was about citizenship. When times were good for him,Coenraad van Beuningen had been the embodiment of the ideal Amsterdam merchant, a typical ‘mercator sapiens’, the Renaissance model of the erudite, citizen familiar with the Classics while simultaneously being able to run a business. A tolerant and cosmopolitan citizen too, because every merchant-city is always tolerant, otherwise no bussines is possible with non-believers. After its relatively short period of prosperity, Van Beuningen saw the wayward Dutch culture of the Golden Age fall prey to lethargy and corruption.

Another part of the crisis had deeper, more international roots. The Northern Netherlands were unique in the seventeenth century. For decades they had been a rich and peaceful kind of island in a turbulent Europe. The country had an incredibly wide trade network, and conducted politics like a large state – all on quite a small piece of land with relatively few inhabitants.

Just as we and the rest of the world talk about ‘the eleventh of September,’ Van Beuningen and his contemporaries talked about the previously mentioned crisis year of 1672. By chance the French invasion was stranded near Utrecht. At an early stage disagreement broke out among the attacking forces, and the young Stadholder William III proved to be a remarkably good strategist, saving The Netherlands. But only just. These events made it clear that the Republic’s successful formula couldn’t last. Its status was a burden the small country couldn’t bear much longer. It was the worst crisis Van Beuningen had feared – the crisis of the end of the unique position of his country and town, the crisis of the uniqueness of his world.

That was more than three hundred years ago. We don’t talk about blood stains, Jacoba or visions of coffins above the Butter Market anymore in The Netherlands. Instead, we watch a daily reality show in which five men and five women, including a mother and children,– and yes, sex, of course – are locked up together in a millionaire’s villa where they can lead millionaires’ lives for at least a year, until they’ve made each other mad and only one remains. Jacoba has become a commodity.

We read about the increasing fundamentalism of Muslim youths, and hear from women friends how Muslim teens yell ‘whore’ at them for cycling openly through town. We see figures from research bureaus and universities – pockets of youth unemployment, truancy and youth criminality in some areas, youngsters of some groups lagging behind in language skills and education, and successful immigrants leaving their original neighborhoods – which sometimes leads to explosive situations between the poor from immigrant communities who remain and the poor native Dutch, who feel abandoned.

We follow the public debate – ten years ago, everything in The Netherlands was about tolerance, but nowadays people using the word are branded ‘multiculturalists’, or worse, ‘traitors’. We haven’t had this much argument since 1672.

We’re amazed about the statistics – in 1999 the percentage of Dutchmen who approved of the government and its politics was 65 percent. Since 2002 that’s dropped to just 35 percent. Never before has the Social and Cultural Planning Office registered such a large change in such a short period of time. We deplore the disappearance of humour in the streets, the natural civil trust that used to bind us and which, at least in my city, seems to have been replaced by a kind of sad nostalgia for the Amsterdam of quiet canals and elm trees, of rattling trams – a closed, private world which seems to have disappeared forever. And we seem to have forgotten that once there was a mercator sapiens.

The last four years have been insane in The Netherlands, that’s for certain – the amazing rise of the demagogic gay populist Pim Fortuyn who was killed by an animal activist days before his election victory; the murder of the Dutch Michael More – OK, Theo van Gogh was a litte more rightwing than the real Michael More but he was the same kind of public figure in Holland; the rise and disappearance of the charismatic African refugee Ayaan Hirsi Ali as a kind of Joan of Arc against ‘the islam’ in the defence of '‘the enlightment’; in the same time, major terrorist attacks in Europe and the rest of the world causing grief, fear and distress in most places but leading to a moral panic in The Netherlands.

Now we harvest the results of these years: opinion polls showed last spring that more than 40 percent of the Dutch want only someone of Dutch origin as a teacher for their child, more than 60 percent thinks that Islam is incompatible with modern life in Europe, half is afraid of the influence of Muslims, and a third openly admits to having become more racist in recent years.

In the middle of the Yugoslav wars I visited the old writer Aleksander Tisma in bombed Novi Sad. I used the word ‘tragedy’ for everything that had happened to his town and his country. But he said, ‘No, these aren’t ingredients for a tragedy, but for a comedy, a farce’. I’ve often thought of him, these last few years. How serious do we need to be about this Dutch illness? Is The Netherlands a European model as far as this is concerned? Is there any reason to shout over the Amstel again, to yell about the ‘unspeakable lethargy’ of the Dutch and, as some do here, about Europe’s weakness in the face of the rapid spread of Islam?

We can talk endlessly about the persons, about Fortuyn, Van Gogh and Hirsi Ali. But more interesting is the context within their stars so suddenly and unexpected could rise, the atmosphere of uncertainty and fear which took over this old, stable nation. I warn you: it is not an easy story of ‘them’ against ‘us’. In fact, it is rather complicated.

In the autumn of 2003, when all of Sweden was shaken by the murder of Minister of Foreign Affairs Anna Lindt, columnist Goran Rosenberg wrote a short essay which I read nodding in agreement 900 miles down the road in Amsterdam. ‘Our country is still mesmerized by its own success story’, he wrote. ‘The history of one of the poorest nations in Europe which developed into a world model of affluence and social care, the history of a small country with a big voice.’ Had the Swedes been rudely awakened from their innocence, as many foreign newspapers suggested? No, Rosenberg wrote. Sweden hadn’t had innocence to awake from for a long time. There had been nothing innocent about the percentages of murders, violent crime, shootings, drug violence and gang rapes for years. What the Swedes had to wake up from wasn’t innocence, but self-delusion, he wrote bitterly, a delusion combining their fear of Europe and the rest of the world, and their nostalgia for a Sweden which had ceased to exist a long time ago.

Rosenberg could have been writing about Denmark, or about The Netherlands. An important part of our misleading self-image is the fiction – our so-called integration policy is full of it – that Dutch society is more or less static, and that the integration of newcomers may be compared to adding a few new colors and flavours to a container of calmly maturing yoghurt. If it mixes well and the yoghurt continues to taste of yoghurt, all is well, or so people seem to think. Nothing could be further from reality. We, Dutchmen of ‘native’ Dutch ancestry, lie to ourselves when we say that we don’t change, that it’s only outsiders who force us to. I recently spoke to a film maker making a film about Amsterdam in 1979. He was desperately seeking locations, but was having difficulty finding them. A costume drama set in the eighteenth century is easier to produce these days, he said, than a film set in the Amsterdam of barely a quarter of a century ago. Nothing has remained the same. It’s more realistic, therefore, to visualize Dutch society as a speeding train which newcomers – youths, immigrants – need to jump up on. And what’s more, it’s a train from the magical world of Harry Potter, a train which, while moving, continually changes both spiritually and physically.

Just like the Swedes, we, citizens of The Netherlands, need to go through a number of painful and complicated transition periods, through situations which can create great turbulence themselves and which, when combined, could indeed lead to the political and moral ‘perfect storm’ which has been raging recently. I will name four. They’re partly typically Dutch, and partly exist in all of Western Europe.

First of all, a typically Dutch situation – the fundamental political and religious transition the country is going through, a transition which is much more far-reaching than that in the merely famous sixties. I use the combination politics/religion on purpose, because The Netherlands was formerly intensely religious and, because of the socio-political ‘pillar’ system it had, political contradictions largely coincided with religious or ideological divides.

Not just politics, but social life was divided this way too. In the small provincial town I grew up in, I went to a Protestant school – the newspaper, the university where my brothers studied, the football club, the scouts, the baker and the milkman were Protestant too. Even the leaves on the trees were, I sometimes thought. The world of my uncle, who was a socialist and taught at the local state school, looked the same, only he bought his bread at the socialist co-op, and the leaves on the trees looked slightly different to him too.

Yet, there was no problem ruling the country. The elites at the top of the pillars made continual compromises with each other. Such was the tradition of what is called the Polder Model. The system as a whole functioned as a very effective pacification machine in this religiously divided country. And, at the same time, created a national community which seemed much more tolerant than it really was, because people simply looked away from each other.

The system came to an end when the Dutch began to leave the churches in droves. In 1958 a quarter of the Dutch claimed to be churchless. In 2020 this will be three quarters. The percentage of Roman Catholics has decreased from 42 percent in 1958 to 17 percent in 2006. The size of the large Protestant church has been reduced by two thirds from 31 percent of the population to 10 percent. It is expected that around 2020 both Protestants and Catholics will be small minorities.

With that, the foundation has disappeared. Since the seventies, many of the old political parties have been abolished or merged, but only now are the consequences of secularization having an impact on political culture.

The Dutch politicians need to find new bases for their policies. And they try to find them, mostly, by turning away from all kinds of religion and ideology. People like the populist Pim Fortuyn were especially angry about the fact that Muslims reintroduced the concept of religion into Dutch public debate because – as Ian Buruma writes in his enlightening book about the situation in The Netherlands – ‘they had just painfully wrested themselves free from the strictures of their own religions.’

My own experience confirms this – contrary to what you would expect, many orthodox Christians in The Netherlands supported the Muslims in this crisis. They recognized their problems and together they worried about this rapidly spreading Enlightened Fundamentalism. Or, as the editor of an orthodox daily once said to me, ‘Today the Minister for Integration provokes an incident with an orthodox Muslim because he refuses to shake the hand of a woman, but next year she’ll ignore me wanting to say grace before lunch.’ In other words, it wasn’t just a clash between the values of the West and those of Islam, but also one between secularism and religion in general.

Letting go of the rigid religious and ideological order, therefore, meant an end to the traditional political truce in The Netherlands. The breakdown of the pillar system created enough space for a phenomenon which has existed in other European countries for much longer: the national populist party, which managed to gain the support of the angry part of the electorate which doesn’t usually vote. Pim Fortuyn, its leader, was the first to manage this. Such an attack on the elite will no doubt repeat itself. Because that too is an aspect of this transition – the pillars may have resolved, but their elites and their successors are still in power. Power, however, which is no longer solidly rooted. The brakes are off.

The second fundamental transition concerns urbanization. Amsterdam and Rotterdam, I can’t stress this enough, are only a small part of The Netherlands. In Coenraad van Beuningen’s time The Netherlands consisted of only one large European city, Amsterdam, and dozens of small and medium-sized provincial towns. The city attracted all the attention, but the heart and mind of the land were located in the provinces and until recently that was still the case. Bourgeois, a little xenophobic yet freethinking, conservative but not offensive. The real Netherlands was Zutphen, Leeuwarden, Roermond. Those were the towns, after all, which provided the decisive election results.

All this is changing. Both the media and politics are increasingly dominated by the cities of Amsterdam, Utrecht, Rotterdam and The Hague, which form an urban ring called the Randstad. This entire ring is in the process of turning into one large delta metropolis not dissimilar to the Bay Area, built around a large piece of protected old polder land which, in the future, may serve as a kind of giant Central Park. Soon more than half of the Dutch population will live in this metropolis – after London, Paris and the Ruhr Area the largest urban agglomeration in north-western Europe. As a result, the relatively provincial Netherlands – even worldly Amsterdam had, for a long time, an air of provincialism about it – is rapidly opening up to the rest of the world.

I remember that after the bomb attacks on the London underground last year, the British newspapers published series of short biographies of the victims. They were often moving accounts of the short lives of office clerks, students, IT specialists, nurses – mostly promising young people from all corners of the world. Unintentionally, though, these pages showed something else: this is what a train carriage in a European metropolis looks like in the morning rush hour. And it’s true, the dynamics and culture which these young people exude, stand for everything that fundamentalists hate. Robert Kaplan talks about the appearance of a world network of ‘metroplexes’ – major urban conglomerates dominated by large waves of immigration and top technology which don’t really need national ‘mediators’ anymore. They’re becoming cosmopolitan cities in the most literal sense of the word. The Dutch Randstad is in the middle of this process. At the moment, a quarter – I repeat, a quarter – of the population of the Central and Southern parts of Amsterdam consists of expats – immigrants from highly industrialized countries. The main language at my bakery changes from year to year. My neighbourhood, my city, needs to find itself in this – in new forms, in a new language, in a new type of citizenship.

The third source of fear in The Netherlands concerns the cathedral of social services to which everyone thought they could always appeal for help. Those expectations, however, are being shattered by the ageing of the population. This problem exists everywhere in Western Europe and, from time to time, flares up like a wild fire. At the moment, the average age in Europe is around 35, 36 – about the same as in the United States. In 2050, however, the average age will be over 50, while in the US, it’ll still be 35 due to the tens of millions of immigrants. Young people are disappearing, which in the long run will have enormous consequences for all European welfare states. At the moment there are still four working persons for every retired one over sixty-five. If policies don’t change, there will be less than two for every pensioner in 2050. Every European country needs to face this reality and find a solution. As Claude Juncker, Prime Minister of Luxemburg said, ‘We do know what we need to do to adapt our social system to the demands of the 21st century, but we don’t know how we can win the elections afterwards.’

Nevertheless, the citizens – used to the safety of their unemployment, invalidity, sickness and old age benefits – feel this insecurity. Thus, more and more Europeans – and this is particularly true for The Netherlands – are falling prey to what Barbara Ehrenreich once poignantly described as ‘the fear of falling’, the permanent fear of the middle classes of losing the status they have worked for so hard, with a good home and a secure future. Significant in this respect is the electoral situation around Amsterdam. Where did most Pim Fortuyn supporters live in the Amsterdam area? Not in the problematic old neighborhoods, but in the neat suburb of Almere, where a middle class with two incomes can barely pay the mortgage. They are, indeed, full of the ‘fear of falling’.

Finally, there is the immigrant, symbol and scapegoat of all worries and frustrations which the previously mentioned changes have caused. Yet an influential phenomenon in itself – in the big cities, at least. First a few facts. At the moment there are about 16 million Muslim immigrants living in Europe. Added to these are the 7 million Muslims who have lived in Bosnia and Albania for centuries. Together that’s about 23 million to a total of 460 million Europeans. Yes, indeed, we are ‘engulfed’ by 5 percent of the European population.

As a result, in large parts of Europe – in the Central and Eastern parts, and almost everywhere in the countryside, also in the West – there are hardly any or no Muslim immigrants. As far as my own country is concerned: officially there are about one million Muslims living in The Netherlands, who make up about 6 percent of the total population. Only, the way they’ve been counted is a little strange – everyone whose parents come from a Muslim country is counted as Muslim. In reality, about a third is still religiously active. A small minority – probably between 5 or 10 percent, figures are difficult to gather – is real conservative, and only a few thousands of them follow fundamentalistic and/or radical leaders.

In the cities, particularly in some neighborhoods in Western Europe, are the muslim-immigrant percentages aren’t one or two, but fifty or more. In a Dutch provincial town as Amersfoort almost a quarter of the inhabitants is now from Maroccan or Turkish descent.

On the other hand, a lot of – and often most – immigrants in Europe are not muslim at all. Let’s zoom in on my own city, Amsterdam. In a year or two, three, the ‘original’ Dutch will be a minority. Does that mean the city is being taken over by Muslims and that the Concert Hall, a temple of Western music, will have to be closed – as former European Commissioner Frits Bolkestein claims regularly?

With all due respect, there is no ground for such panic. Look at the figures. Of the more than 700,000 Amsterdamers, not even 120,000 are from Muslim countries – Turkey and Morocco in particular. The majority of immigrants, more than 250,000, is from elsewhere: Surinam, Indonesia, the Antilles, Germany, England, the rest of Europe, the US. There are considerably more expats from industrialized countries than Moroccans – more than 70,000 compared to more than 60,000. It’s true that Amsterdam is fast and rigorously ‘de-Dutchifying’. However, we aren’t seeing the emergence of a Muslim city, but of a cosmopolitan metroplex as described by Robert Kaplan.

Do those Muslim minorities manage to integrate into that modern urban system, though? Some Dutch authors speak of a ‘multicultural’ disaster, but when American city sociologists like John Mollenkopf and Julius Wilson visit The Netherlands, they burst out laughing. ‘What? These are your ghettos? What a lucky country!’ Who is right?

I would like to start with the term ‘multiculturality’. You can be positive or negative about it, but the time of dreamy theories is long gone. The Netherlands as a whole doesn’t have to and, indeed, will not become multicultural. On the other hand, large parts of Amsterdam and Rotterdam have been multicultural already for years. What’s more, if you talk to pupils there, students, party-goers, people in their late twenties or early thirties, you’ll find that no-one talks about multiculturality. For them it’s not a Utopia, but it’s no disaster either. It’s a natural fact they’ve been living with all their lives. They play football with Turkish friends, write their thesis with Hindustani fellow-students, and are astonished by the incredible pace at which the head-scarf wearing girls of Turkish- or Moroccan-descent study, apparently determined to catch up on two centuries of emancipation.

So there is no multicultural disaster going on. Figures from the Amsterdam Social-Cultural Studies Bureau show that, with regard to the age at which people marry and have children, the younger generations of Muslim immigrants increasingly resemble the Dutch. The fall in the number of children is spectacular, from more than eight in the first generation to less than four in the second. The average level of education has improved enormously compared to the widespread illiteracy of twenty years ago and is similar to that of Dutch people from similar income groups. There are no ghettos to speak of and the social maps of the richer suburbs increasingly show small pockets of Turks – a sign that this group is joining the richer middle classes. In other words, at various levels the integration of Muslim immigrants in Amsterdam isn’t bad. In many respects, it’s better than in Rotterdam or The Hague, cities which are much poorer, have cheaper and poorer-quality housing and have the most problem areas.

This is not to say that there are no serious problems, and even the relatively smoothly-running emancipation machine of Amsterdam has its defects. The Americans grinned when they saw our ‘ghettos’, but they did notice something else. The rate of integration in terms of work, language and education was astonishingly low.

In 1998 John Mollenkopf, professor of Sociology and director of the Center for Urban Research of the City University in New York, conducted an extensive study into the differences between Amsterdam and New York. His conclusions were eye-opening. The average immigrant in New York has a better job and a higher social position in a shorter period of time than the one in Amsterdam. After ten years, the children of the New York immigrants do better at school and university than the Amsterdam ones do after twenty-five. The figures of criminality among some groups of young immigrants are strikingly high in The Netherlands, and there is little contact between newcomers and those who have been living in the country for a while. In my opinion the situation improved considerably, the last years, but still: how can we explain this?

John Mollenkopf suggests that the good social facilities in The Netherlands have unintentionally played an important part in the slow integration of these groups. Work is still the best way of integrating fast. In The Netherlands, however, people aren’t pushed to the limit to take part in the process of employment. In other words, there are too many opportunities in The Netherlands to avoid work and integration.

Another cause is, no doubt, the difference in identity between Amsterdam and New York. A New Yorker is always a kind of an immigrant, even when his family came here centuries ago. Immigration is the rule in the country. A Dutchman sees himself as a native, someone who has lived in this place since the creation of the world, and immigrants are always the other, the exception.

Then there is, of course, the nature of this modern wave of immigration. During the golden years of Coenraad van Beuningen there were also large groups of immigrants who came to settle in the city. Seventeenth-century Amsterdam was already a kind of American melting pot and the vernacular changed from broad Northern Dutch to the broad Antwerp dialect within a generation. But things are different today. The Turkish and Moroccan immigrants who arrived in the sixties and seventies of the twentieth century came largely from small, poor, traditional villages in Anatolia and the Rif Mountains. They were often illiterate, didn’t speak a foreign language and were invited only to fill up some gaps in the labour market. Neither the immigrants themselves nor the Dutch government intended them to migrate permanently. They weren’t suitable for that. The difference between their closed, tribal village life and the postmodern urban society of The Netherlands was much too great. The problem, therefore, was not so much one of Turkey and Morocco versus The Netherlands, or Islam versus the West, but one of the enormous gap between countryside and city – a problem which, by the way, exists in all rapidly modernizing societies.

The situation was exacerbated by the fact that The Netherlands, as opposed to a classic country of immigration like the US, had and has no rituals to welcome immigrants and give them their own space. What’s more, both parties, newcomers and established inhabitants alike, have endlessly postponed the real – psychological – immigration and integration.

I once asked a few students of Turkish descent when their parents had decided to stay in The Netherlands for good. As they were born and bred in The Netherlands, I expected the decision to have been taken in the early nineties. But no, they talked about four, five years ago. For at least a quarter of a century these families had lived with the ‘myth of the delayed departure’, with the illusion that all would be temporary. Both the immigrants and the Dutch had their own motives for this, because neither party wanted this immigration. This vague situation was exacerbated still further by the atmosphere of jolly tolerance which was popular in wide circles in the seventies and eighties. Even the ‘tough measures’ with which people wanted to ‘solve’ the problem afterwards were based on the same illusion – immigration doesn’t have to exist, not even in a modern transitional society like the Dutch one. We simply close our borders as much as we can. Only insiders – neighbors, the police, social workers, some journalists – knew that there was a time bomb ticking away.

What is the relationship between these problems and Islam? There are politicians and panel members who believe that most of these problems are based on religious matters – Islam and modernity just aren’t compatible. With all due respect, I dispute this. Did we ever have serious integration problems in Amsterdam with Muslims from Istanbul or Sarajevo? Or with the thousands from Indonesia, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran and Egypt?

Certainly, Islam is struggling as a religion to find a new place in modern times, and Europe has unintentionally become a frontline in that struggle. In that sense there are religious and cultural contradictions and clashes involved, particularly focusing on the relationship between men and women. There were – and will be – very necessary debates about western values and the values of the islam, debates also about secularism and religion, and about Enlightment and the sharia. And, above all, about the question: which are universal values, and which are values belonging to our different cultures?

It is a deep, difficult debate which is going on nowadays within almost all westeuropean community’s: which are exact our common values? And which of these values are so universal that we have to impose them on all citizens, immigrants and non-immigrants? To abstain from physical violence? For sure! To guarantee freedom of opinion? Yes!To maintain the same basic-rights for every human being, men and women? Of course!

But what about a certain kind of dresses? And is for instance the tradition of the Enlightment the one and only universal heritage of the European society’s? Are there no Christian values, no Humanistic values, no interesting other values in our Dutch and European tradions? Is ‘our values’ not a complicated question for ourselves too?

There’s another matter countless immigrants – Muslims and non-Muslims – are confronted with: the inner focus on the home country. This focus often tends to freeze. People don’t change with developments in their mother land and their home world remains frozen in the situation of 1975, 1963 or 1948 – a situation which is clearly noticeable with, for instance, Dutchmen who emigrated to America, Australia or South-Africa in the fifties. The beliefs held by Dutch colonists in Grand Rapids are now only found in some villages in Central or South-West Netherlands. You can see the same thing in problematic neighborhoods in The Netherlands. Older immigrants particularly, from Turkey and Morocco, increasingly create an imaginary homeland which, in reality, no longer exists. You would think that Islam modernizes faster in Europe than in the homelands but it’s often the other way around. This has little or nothing to do with the capability or incapability of Islam to adapt, and everything with this cultural side-effect of immigration itself.

The problems which some groups of Turkish and Moroccan descent face aren’t simply a matter of religious differences. Sometimes they’re bigger and certainly more complicated. This ‘religieous’ theory’s, moreover, have far-reaching consequences:Muslims have to convert to some kind of enlightened secularism and if they don’t, which you can expect, they’re excluded from the modern world and integration into Western countries. In a city like mine that means that about one sixth of the population is excluded and written off, in effect, resulting in a huge escalation of insidious tensions – nationally and internationally. Muslim-immigrants will never feel at home, will never integrate normally. In other words, the politics of religion is leading nowhere. As the Nestor of Amsterdam sociologists, Prof. Abram de Swaan, once said, ‘The least interesting thing about our Islamists is Islam’.

Every wave of immigration and every process of integration comes with friction and problems. But why did this get so out of hand in the open, tolerant Netherlands? Why this fog, this confusion, why this fear of the word ‘immigration’? I can think of only one explanation – it was the only way to avoid our own inner conflicts starting with the Second World War, in which Amsterdam tolerance failed to keep thousands of fellow citizens from being deported and killed. It wasn’t surprising, therefore – particularly in a city like Amsterdam – that people were intensely sensitive about soiling the collective conscience with group hate, and that there was great fear of recurring racism. Those who label this ‘political correctness’ are deaf to history. However, our post-war ethics increasingly clashed with the reality of the years around the turn of the century.

Every nation is essentially an ‘imagined society’, anthropologist Benedict Anderson once wrote. For decades, our Dutch ‘imagined society’ was based on concepts like ‘civil solidarity,’ ‘tolerance’ and ‘openness’. With those, after all, we had become a rich and happy country.

With the arrival of more and more immigrants, however, we became increasingly at odds with our own principles. The principle of solidarity, for instance, gave us the warmth of a welfare state. But if we would then, on the basis of that same principle, share our wealth with newcomers from elsewhere, it would mean the end of that same welfare state. The openness, another characteristic of this trading nation by the sea, became threatened by a new fundamentalism which had entered our country as a result of the same openness. And similarly our tolerance, like former Amsterdam mayor Ed van Thijn predicted years ago, could kill tolerance. These were difficult dilemmas, but for years they could be avoided by making the word ‘immigrant’ taboo. Although they knew better, government officials and the media kept using terms referring to a temporary immigration, terms like ‘migrant worker,’ ‘foreign-born,’ and ‘asylum-seeker’ – synonyms of ‘not thinking,’ ‘delay,’ and ‘pussyfooting around’. The immigrant as an ordinary neighbor, immigration as an unavoidable and even necessary phenomenon, the demands that every normal society put on immigrants, the open conflict that comes with it – it was not to be.

The debate about immigration and integration says a lot about Dutch society, about hope and fate in ourselves and each other, but also about the opposite – about the moral panic among mostly the older generations of the Dutch. One of the historical patterns we have to get used to again is that things can take another turn than we expect, that achievements may disappear and that such loss isn’t temporary, but permanent. Part of our civil crisis is about mourning.

I have a friend, René van Stipriaan, with whom I talk a lot about Dutch culture of the seventeenth century. We both enjoy it. He’s a historian and specialized in it, and I find it incredibly interesting. He made me aware of something odd. Around 1780, almost a century after Coenraad van Beuningen, every erudite citizen of Amsterdam still knew the etiquette, the hidden symbolism in paintings, the religious references and all the other codes of seventeenth-century Amsterdam culture. Half a century later, around 1830 – two generations down the line – that knowledge had disappeared. The Golden Age became a black hole into which, without much opposition, all manner of nationalist bombast could be projected onto. Only since the late twentieth century have historians been struggling to reconstruct the seventeenth-century way of thinking. Very slowly, Van Beuningen is coming back to us.

I have a strong sensation that we are living in a similar period, and I say this without pleasure.

During a large part of the previous century the Amsterdam and Dutch mentality was dominated by a Jewish, Humanist, Christian culture, a fertile mix of socialism and liberalism rooted in the ideas of the Enlightenment. It’s a frugal, intrinsically rich culture which I grew up in and which I love. A culture which most of the Dutch take for granted, which they don’t consider exceptional, but which is, in fact, unique. It’s a civilization which we only recognize now that it’s threatened. The older Dutch have been brought up with it, the younger generations know its values and symbols to a greater or lesser extent, but will their children and grandchildren in half a century? That seems uncertain.

So we mourn a lost sense of security. We mourn lost neighborhood communities, a lost sense of togetherness, although this was already happening when the first immigrants arrived. We mustn’t forget that. Some mourn the disappearance of the ties based on common religious, political and nationalist feelings, the sense of identity that came with it and which is disappearing or has already disappeared.

There’s a limit to the mourning, though, because our national identity – that of an open country in North-Western Europe – just can’t be put under a protective glass cheese cover. It wouldn’t work. Other things are more important: self-confidence, citizenship, individualism, determination, the will to accept the facts and be part of our new country.

This is also where people try and retain, for example, the principles of our European tradition, Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Humanism, Englightenment, Romanticism, this entire rational, free and at the same time humane and spiritual way of thinking. They’re trying to hold on to the constitutional state and democracy – formerly an inextricable part of this special Dutch citizenship – values that now threaten to degenerate into mere formalities. And they’re holding on to good education, which should pass that common cultural heritage on to the next generation.

I spoke with my former colleague Paolo de Mas recently. Working for the University of Amsterdam, he has spent years following a group of immigrants from a small area in Morocco. His observations confirm the picture I’ve been painting this last hour – ‘his’ families have integrated better into Spanish, French, German and Belgian cities than in Amsterdam. He said, ‘If these groups had moved to The Netherlands in the early fifties, it’s likely there would have been very few problems. They would have easily found a place in the pillar system that existed at the time. Everything was still clear. Everyone went to his own church on Sundays, roles were clearly defined. If you drove through a red light, you got a ticket, if you didn’t pay attention at school, you got a slap. It was a recognizable society for everyone, also for Moroccans from a small village. Compared to the rest of the world, The Netherlands, and Amsterdam in particular, became exotic after the sixties.’

But Paolo de Mas had good news too. He also said, ‘I was lying on a Moroccan beach recently, and I could immediately identify the holidaying Dutch Moroccans. That’s how much they’ve integrated by now.’ I asked, ‘How did you know?’ He said, ‘Very simple, from the children’s behavior.’

Am I, in the end, optimistic, too optimistic perhaps about the developments in The Netherlands? Am I this famous frog, which let himself boil in slowly heated-up water, to drowsy to make a jump out. Not when it concerns the islam. There are problems, sure, with some small groups of muslims, specially the young boys from Maroccan descent. They can do harm, indedd, but they cannot change a whoe society.

The real problems in The Netherlands and Europe are nót theological problems, but social problems, immigration problems, city problems, economical problems, political problems. And I will not, and I cannot, these questions redefine in terms of ‘enemies’ who ‘ínvade’ our cities and ‘take over’ the European society’s, as some suggest.

The public debate in The Netherlands will, I expect, change soon to a total other subject: the climate changes, the rainfall problems and the rise of the level of the sea. For, in the end, Holland is a kind of Bangla Desh, a rich and modern Banla Desh, but still a Bangla Desh. We have to pay most of our attention just on our physical survival.

And we can, and we will. Because underneath all that turbulence there’s still an old, solid, reasonably stable civil society. So strong, in fact, that despite lacking the will to immigrate and the lack of immigration policies, despite the cultural gap between countryside and city, despite the religious differences, despite the turbulence and discrimination of recent years, it has managed to convince and hold on to the majority of immigrants and immigrant youth. Because that’s what you hear too little about, about all those teachers, lecturers, neighbourhood councillors, local policemen, social workers, housewives, and all those, immigrants and non-immigrants, with courage, a sense of responsibility and endless patience, who are, indeed, keeping our cities and country together. That’s the great, fundamental power of these times. The Netherlands is changing, changing a lot, but it isn’t disappearing. Even if Coenraad van Beuningen loses his mind.

Thank you very much.

This lecture was given by Geert Mak at the universities of Harvard, Berkeley, the UCLA and a few other places during a roundtrip in de USA, autumn 2006.